Diana Kennedy: The memory of taste Ep.58

Presented by: Rocio Carvajal Food history writer, cook and author.

Episode 58

There are only but a handful of people in the world that have literally devoted their lives with an unconditional passion to studying and understanding specific culinary traditions, so much so that their works are undisputed sources of reference and have become roadmaps to study those cuisines.

But cookbooks you see, are not the only type of food writing there is even if recipes are mentioned in them, and because of the relatively recent appearance of the discipline of food studies there are still some blurred lines around the way we see different types of food writing genres and that’s how we end up finding books by the likes of “Mexican microwave cookery” next to Diana Kennedy’s “The art of Mexican cooking” on the same shelf.

If you are a Mexican food enthusiast you have probably already listened to episode 55 where I featured a conversion I had with Elizabeth Carrol, the director of the critically acclaimed documentary Diana Kennedy: Nothing fancy, and hopefully many of you have also had the opportunity of streaming it, and I know that many of you have some of Diana’s books. The premiere of this film has pushed a renewed interest and sense of alarm upon making known to the world that this Diana a Mexican food evangelist is almost a 100 years old and perhaps the world has not yet quite begun to understand the depth, value and impact of her legacy for Mexico and the culinary memory of the world.

I’ve also noticed that much of what has been written recently about Diana revolves around her personality, and attitudes towards her opinions about the way she insist -people should understand traditional Mexican food and she is described with adjectives that go from “uncompromising” to “dogmatic” underlying that she has little patience for people who over-interpret and feels the need to adapt traditional food for “refined tastes” which she sees as the bastardisation of Mexican food.

And while all of that is true, I’m not really interested on dwelling on comparisons for the sake of it, instead, in this episode I aim to explore through a serious of questions how can we better understand her work, what does it actually consist of, what it impact has had for Mexico and the world, and how her books can provide an entirely different reading if we approach them with a different perspective. Sounds good no?

So what is food writing?

I think this question is a good starting point, because we seldom stop and ponder about how previous generations thought, felt and wrote about food, so let’s see some milestones of how writing about food evolved (in the western world) and I will point out at some of the main characteristics of the main categories.

For hundreds of years, cookbooks were pretty much the only type of works where food was the main subject and it was addressed namely through recipes, writing them down came from the need to preserve the methods, techniques and recipes when memory and oral tradition weren’t enough. Handwritten scrapbooks and printed cookery books were for centuries the main way of learning about other cuisines, and recipe writing was mainly done by male chefs and housewives for an audience that was primarily made up of female home cooks.

In recent decades there has been an explosion of cookbooks that have created many sub-categories to cater for a fast-growing wider audience, and we can find historical cookbooks, collections of recipes based on literature works think Jane Austen-inspired tea parties or Harry Potter desserts, the rise of the tv and internet celebrity chef cookbook and of course now every restaurant and cafe must have their own cookbook as part of their marketing strategy and business model and to build their reputation and visibility, where even cookware and merchandising are part of it think of Rick Bayless or Nigella Lawson.

But going back to our timeline, something happened in the post-war period in the late 1940s, while Europe was beginning to get back on its feet and returning to a new normality which also meant much to the relief of many, stop eating rationing food. One English author by the name of Elizabeth David started writing about the exotic French Mediterranean coast, and describing vividly the food, people and landscapes of Italy immediately capturing people’s imagination with the idea of those wonderful flavours and aromas, and with that, the food memoir was born, where travel, eating, first-person narratives and recipes were all blended together. Elizabeth David’s books were hugely influential, inspiring a whole generation to open up to other cuisines, Diana Kennedy was one of such readers who was immediately fascinated by this.

Food memoirs opened up new possibilities for those who became aware that food was something that people were actually willing to read about food and that it wasn’t only focused on recipes but the experience of preparing and eating food that was worth writing about. Newspapers and magazines started including columns and articles about people’s experiences eating at restaurants, talking about wines, or food events, interviewing cooks and producers and letting people know their opinions and recommendations about them, and that became the genere of food journalism, which we still read today on specialised publications, podcasts, television, films and blogs.

And then many counterculture movements happened that sent shockwaves through all aspects of life, there are two books that are considered to be groundbreaking as they completely revolutionised the way we see food, coincidentally the authors are both French: one of the books is simply titled Mythologies by semiotician and philosopher Roland Barthes, and Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste by anthropologist, sociologist and fellow philosopher Pierre Bourdieu. To make a long story short Barthes pointed out that food is the carrier of our beliefs, preferences, ideologies, spirituality and that a single food can have many meanings, Bourdieu on the other hand rises the issue of how class, race and education create a specific cultural capital and that taste and food have a language of their own that expresses power, control and behavioural rules, for instance he demonstrated that bread can be the ultimate religious metaphor, the humblest of foods, a carb-loaded enemy and the ultimate synonym of togetherness. These works made us aware that the rapidly evolving advertising industry had already mastered way before we even realised what was going on the fine art of shaping our perception about foods and drinks, creating narratives that made us aspire to a emulate a lifestyle by triggering with advertisement campaigns our emotions and shaping our identities. So these two authors along with many other academics shaped what it would become known as food studies.

Quick note: parallel to all of this changes in food writing, governments and multinational organisations like united nations also started focusing on food from a very different perspective like: food security, policies, nutrition, agricultural systems and other related areas.

Going back to food studies, this fairly new and promising field of research took shape by borrowing methods and tools from history, philosophy, sociology, anthropology, biology, semiotics and quite a few other disciplines, the works produced from this field went from being incredibly complex and aimed to an academic audience to recognise that we all could do from knowing, understanding and learning to see the role that food has in our social life, economics, politics, religion and so on. And chances are that many of you have already been exposed to this type of work, a good example is the book Cooked: a natural history of transformation by Michael Pollan that was also adapted for a Netflix series, TED talks, articles… even and I did a review about it on my Podcast Hungry books.

So the reason why I took the time to give you this context is that, in my opinion, food studies are the category in which I would fit Diana Kennedy’s work for its richness, scope and meticulous research among other things, and in the rest of the episode I’ll tell you why by taking a closer and look at her work and giving it more context.

Life is indeed full of serendipitous events, choices and circumstances that shape and re-shape our decisions and opportunities. Europe in 1942 was at the brink of war and if you think our lives have turned upside-down because of the ongoing health crisis we’re living now, an actual war is quite a different scenario, so back in England when Diana, who came from a working-class family and was only 19 by the time she should have started college, she became instead a lumber Jill, that is she joined the Women’s Timber Corps, which was a branch of the Women’s Land Army that recruited and trained women during the Second World War to perform jobs traditionally done by men. The Timber Corps were managed by the forestry commission and their duties went from operating sawmills, managing woodland and pretty much keeping the timber industry functioning. And these are pretty much the types of experiences that would give you a lot of self-confidence and shape your character for life.

Women Lumberjacks Issue Title – Jolly Good Fellers (1942)

Some decades after the war when Diana Southwood came to Mexico in 1957 at the age of 34 with her future husband Paul P. Kennedy whose she met him previously during a trip she took to Haiti while he was covering the turbulent social and political events at the time. It didn’t take them long to get together and swiftly decided to settle in Mexico when her real close encounter with Mexican food happened and quickly realised that the food served at tourist’s restaurants was absolutely different from what Mexican people cooked at home, ate at traditional eateries, street stalls and markets and this was a true culinary shock and awakening, and like in many other situations before in her life, she didn’t back off, if anything she ran towards it, and in spite of not really speaking Spanish, she quickly found her way around getting familiar with the foods, flavours of Mexican food and sooner rather than later also attempting to cook it. While back in the 50s 60s in there were plenty of supermarkets in Mexico City, of course, traditional markets, big and small were just like today the best cost-effective way to buy fresh produce, groceries, meats and even ready-made food, crockery and other cooking utensils. Through many interviews and her own books she shares how she became fascinated by the variety of edible herbs, fruits, chillies and vegetables that she had never heard of before and finding more about these ingredients became for her the entry point to understanding the deep connection of Mexican food between aspects such as seasonality, agricultural systems and the gastronomic traditions of the many cultural regions, and as you can see now, these are things that you can only really notice if you spend weeks, months and years observing, interacting with people and asking a hell of a lot of questions.

Paul Kennedy who became Diana’s husband, was a journalist who worked as a Latin America correspondent for the New York times, and as is often the case in famous couples people tend to know way more about either spouse, so let me tell you a bit about Paul, he had done extensive work covering and analysing the political and armed conflicts of this region in a particularly complex historical time where guerrillas, US military interventionism, international espionage, several coup d’etats, revolutions and economic miracles were all happening at the same time, and he was regarded by the foreign press and academics as one of the world’s leading authorities on this region, so by the time married Diana and settled in Mexico in 1957 Paul had already given her a good head start into having a broad understanding of the social, cultural and political life of the country.

Diana and Paul had a very intense social life, partly because of their jobs as she also became a contributor of the Times and that gave them access to social circles where they befriended diplomats, fellow journalists, artists, writers and people from all walks of life, she often accompanied Paul on assignments to different states and cities across Mexico where she became deeply fascinated with the regionality of food traditions and as her Spanish improved she was able to talk more confidently to cooks, farmers, butchers and people at markets.

During an interview with Sarah Greenberg for the Guardian back in 2003 Diana shared that in the early years of her marriage when they were often invited to parties at their friends’ houses she would ask the hosts for the recipes of the delicious food that was served only to be sent between laughs to talk to their maids who would tell her that she’d be better off visiting their hometowns to really see how those dishes were cooked, which she did with an evangelical passion.

Now, Diana is often described as the saviour of Mexican food, the truth is that grandiose titles can be slightly misleading and tend to find themselves out of context which can be problematic, so let’s unpack that idea, one of the things that Diana quickly realised is that there wasn’t such thing as a national cuisine and trying to describe “Mexican food” under one concept was nearly impossible because food, like many other cultural aspects of Mexico is incredibly tied into the traditions, geography and history of each region and she noted that food is also central aspect of the social life of communities. She refers time and time again in her books that the survival of food traditions, techniques and recipes in Mexico tend to rely largely on oral transmission and an intimate personal interaction to pass on this knowledge form person to person and recipe scrapbooks or cookbooks have little to no use for several reasons, first the belief that learning how to cook implies much more than the correct treatment of ingredients it is about ensuring that the next generation becomes the new custodian of centuries-old traditions. Also and equally important, rural Mexico in the 1960s and 1970s was very impoverished with virtually minimal to no access to education and literacy.

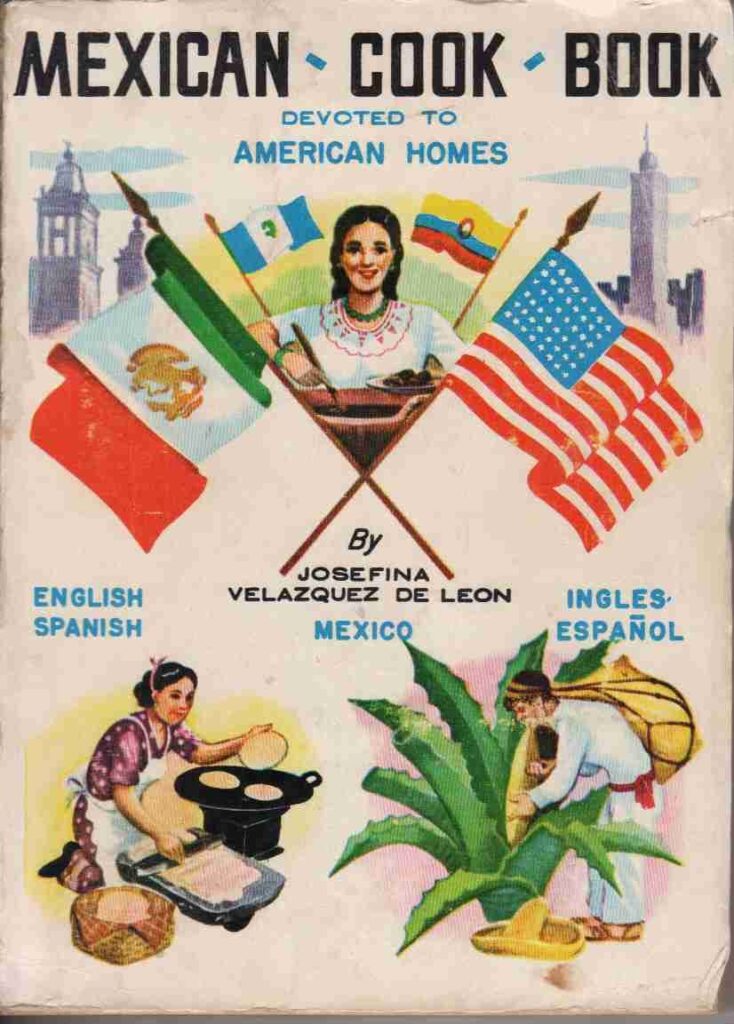

By contrast in large and affluent urban centres like Mexico City middle and upper-class young ladies were expected to be competent housewives, cooks and hostesses, so finishing schools were an essential part for raising the chances of a good marriage for these girls, and here I want to introduce you to a key figure of the culinary world in Mexico. The most famous cooking school where home economics and household management were also taught were those created by Josefina Velazquez de Leon an Aguascalientes born woman who made a name for herself after moving to the capital where she became rapidly known among the well -to do society for her cooking skills and deep knowledge of methods, ingredients and recipes that went beyond the usual dishes preferred by the upper and middle classes, very much in the style of the famous Isabella Beeton, Josefina also researched and complied hundreds of recipes that were published in more than 140 books with irresistible titles like: “Cooking for the newly wedded bride”, “Yucatecan Cuisine”, and “Mexican food devoted for American homes” but there were two key elements to her work that made her a hugely influential personality by the likes of Delia Smith or Martha Stewart: First, she had a very entrepreneurial vision so she quickly embraced the use of technology to speed up processes working with famous brands of pressure cookers, ovens, blenders, stand mixers and other kitchen appliances which she pushed through her tv shows, radio and printed press. She opened up two schools under the name of Velazquez de Leon Cooking academy where she personally delivered many of the classes.

By contrast in large and affluent urban centres like Mexico City middle and upper-class young ladies were expected to be competent housewives, cooks and hostesses, so finishing schools were an essential part for raising the chances of a good marriage for these girls, and here I want to introduce you to a key figure of the culinary world in Mexico. The most famous cooking school where home economics and household management were also taught were those created by Josefina Velazquez de Leon an Aguascalientes born woman who made a name for herself after moving to the capital where she became rapidly known among the well -to do society for her cooking skills and deep knowledge of methods, ingredients and recipes that went beyond the usual dishes preferred by the upper and middle classes, very much in the style of the famous Isabella Beeton, Josefina also researched and complied hundreds of recipes that were published in more than 140 books with irresistible titles like: “Cooking for the newly wedded bride”, “Yucatecan Cuisine”, and “Mexican food devoted for American homes” but there were two key elements to her work that made her a hugely influential personality by the likes of Delia Smith or Martha Stewart: First, she had a very entrepreneurial vision so she quickly embraced the use of technology to speed up processes working with famous brands of pressure cookers, ovens, blenders, stand mixers and other kitchen appliances which she pushed through her tv shows, radio and printed press. She opened up two schools under the name of Velazquez de Leon Cooking academy where she personally delivered many of the classes.

Josefina really pioneered the research of regional cuisines in Mexico, at a time when class divisions were very much evident and even more so through the foods eaten by indigenous, mestizo and aspirational whiter middle classes. She championed festive dishes from different cities, introduced ingredients, techniques and even new vocabulary in her cookbooks. While the interest in regional and local foods had made its first appearance by the end of the 1800s through cookbooks, she used her modern multimedia platform to really amplify the idea that there was much more to be discovered about Mexican food.

But going back to Diana, after living what she has described as very happy 9 years in Mexico, Paul was diagnosed with cancer and sadly died soon after they moved back to NY in 1967, just one year before the terrible student massacre in Tlatelolco, Mexico days before the 1968 Olympic games. In In NY Diana was encouraged to start giving Mexican cooking classes at her apartment which she did as well as teaching at Peter Kump’s New York Cooking School while continued writing for the New York Times. Even at this very early point, Diana had already awakened the curiosity of Americans who were the primary audience of her journalistic work and the impact didn’t take long to be noticed, so much so that in 1971 the Mexican tourism board presented her with a medal as a recognition to her contributions towards promoting cultural tourism in Mexico.

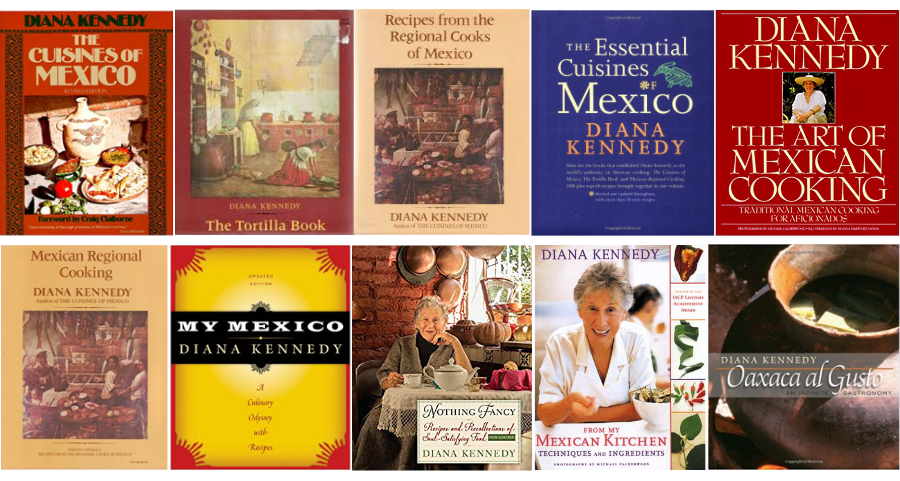

Around this time, she was persuaded by her friend and boss Craig Claiborne the food editor of the NY Times to write her own cookbooks capturing her life in Mexico, Claiborne had a sharp eye for seeing the writing talent and potential of women by the likes of Mary Frances Kennedy Fisher and Julia Child, Diana agreed and started working with editor Frances McCullough on her first book: The Cuisines of Mexico, which was published in 1972.

And It was actually at this point when Diana started Reading Josefina Velazquez’s books for the first time and they had a profound impact in her further comprehension of the regionality of food traditions in Mexico as she has mentioned numerous times, and those books reinforced in her the idea that she had to travel, see and taste to understand it all. So she started doing long research trips in Mexico and soon after she published “The Tortilla Book” in 1975, and after that she was done with New York and decided to move back permanently to Mexico in 1976, two years later “Recipes from the Regional Cooks of Mexico” was released, and in 1980 she bought a property in Zitácuaro Michoacán and in a very Mexican style she named her little rural estate “Quinta Diana”, by then she was already a household name in the international culinary world and a string of honours proceeded including one from the Mexican Food Writers Association, the prestigious Order of the Aztec Eagle was presented to her in 1981 and in 1984 the tourism board again honoured her work with a Jade Molcajete, that is a Pestle and mortar, just when her book “Nothing Fancy (a book of personal recipes)” became an international sensation.

There are literally thousands of articles, interviews, essays, and all sorts of works written about Diana, a simple google search of “Diana Kennedy cook” gives you more than 14,000,000 results and yet people can’t agree on what to call her, how to categorise her books and even amazon reviews often seem to reflect peoples’ confusion with descriptions like: Awful vanity project that lacks the inviting warmth of other cookbooks like Jamie Oliver, another person saying: The recipes are unfailingly interesting but not likely to find much use in American kitchens, someone else thought that: [These] Recipes aren’t necessarily hers and she admits she culls them from other sources, [they are] unusual and not what I would cook, and last one person who wasn’t impressed at all said: Some okay recipes.

The point of course is not to shame any opinion, but to think of the reason why people expect her books to be easy to follow, simplified, coffee-table cookbooks and why wouldn’t they expect that if bookstores insist on putting her books next to Rick Bayles or Thomasina Miers?

So what exactly is Diana’s work about and why it is different? A good phrase to begin exploring this is one by book editor Guillermo Osorno who said that Diana’s work is a testament for Mexico’s food because “it is a window to the memory of taste”. At the top of the episode when I talked briefly about how food writing appeared in the form of cookbooks and form there rapidly many other types of works about food offered different perspectives by seeing food as a conduit for social dynamics, expressing world views, well studying these transformations will help us see that while at first glance the earliest work of Diana might fit in a sort of food memoir category where she passionately shares her admiration and profoundly meaningful experiences travelling and learning from home-cooks about techniques and ingredients, but as her writing evolved we see that she added more layers to that and included in the introduction of each section the meanings of certain dishes as explained by the cooks she interviewed and what it meant for the families and communities, from the very beginning of her book writing career she particularly was careful at letting us who her sources were, about the places and circumstances under which she obtained the recipes she presents.

And as her knowledge through her travels, encounters and research became more complex it reflected on the way she observed and captured all the subtle cultural nuances of celebrations, practices and idiosyncrasies about cooking and conviviality with the precision of an anthropologist, and highlights social dynamics like a true sociologist would, but there is one recurrent aspect that is present thought all of her work and that is the importance of the ingredients, their cultivation, selection, preservation and use, and she achieved to perfectly identify the central role of agriculture has in the identity and way of life of indigenous and rural communities, and l dare say that this is something no other foreign writer and very few Mexican cookbook authors have achieved, she makes that clear connection and instead of entertaining readers with easy tacos and tamales what she presents is her research of Mexico’s cultural and biodiverse and food system through its food.

At this point you might think that I am pushing a bit too much, and I hear you, but remember I told you how Diana’s experiences as a Lumber Jill during WWII were seminal for her future?

Check what she says around minute 5:

Diana Kennedy: “56 Years of Traveling, Cooking, & Writing in Mexico” from madfeed.co on Vimeo.

For five years the Institute of Biology of the National University of Mexico, and the National Commission for the Knowledge and Use of Biodiversity (CONABIO) by its Spanish acronym, worked on a project processing and analysing the result of 50 plus years of material compiled by Diana, the study of her archives included her field notes, photographic material, specimen samples and cataloguing the edible, medicinal and utilitarian native plants that she had collected and cultivated in her own botanical garden at Quinta Diana.

This ambitious project that took two years of fieldwork between 2010-12 and three years more to produce a range of resources and documents is particularly focused on the changes in cultural practices, use and abandonment of certain ingredients and the causes for this, the change of the use of land and loss of traditional agricultural practices that have lead to the endangerment and extinction of dishes and other uses of plants that were previously cultivated or foraged.

One of the main goals this project was to create a catalogue that reflected Diana’s deep knowledge on the ethnobiological resources and uses of the products from the three ancestral agricultural centres of Mesoamerica, their heritage crops, forms of use, cultivation, changes and identifying ingredients of vegetable origin that are at risk of being lost as well as analysing and study the environmental, cultural and dietary impact of the use of genetically modified seeds, pesticides and industrial agriculture.

One of project’s reports mentions that: The conservation of edible plants and its cultivation at their places of origin will help us contribute to the continuation of community rituals and food practices at the face of the threats faced by Mexico’s traditional agriculture that puts at risk forms of life, the equilibrium of the environment and ultimately the nation’s food sovereignty. This pretty much reflects how many specialists, cooks, academics, scientists, anthropologists and communities perceive, value and dimension the impact and relevance of Diana’s work and certainly this is the way I see it too.

Much of the results of this ambitious project known to the public as “Diana Kennedy, the roots of Mexican cooking” and on the you can find videos, information and documents which have free access. (They are all in Spanish but you can use an online translator)

Beyond the undoubtedly well-deserved accolades, ceremonies, medals, titles an honours including being appointed as a Member of the Order of the British Empire, Diana has never been distracted by that, quite the contrary, she has used that to amplify her message without withholding any strong opinion or criticism which might make many people uncomfortable which I don’t think she’s particularly bothered about, she’s been clear abut the fact that she’s not interested in fame or cultivating her image, and ultimately as Chef Gabriela Camara puts it: what matters is that Diana feels the weight of the grief and the tragedy of having accumulated all that knowledge and that it needs to be heard and put to use, because people need to know about it and she carries that as a moral duty. It had been a long dream of Diana to transform Quinta Diana in a gastronomic research centre, but as you can imagine the logistics of that aren’t quite easy, let alone the fact that nowadays Michoacán is at the centre of the most dangerous drug-cartel activity in the country.

During the interview I recorded with Elizabeth Carrol the film director whose debut as a documentarist was precisely “Diana Kennedy Nothing Fancy”, among other things we talked about what transpired during the filming about Diana’s thoughts regarding the future of her work, her house and archives, and we mentioned that at the beginning of 2020 back in February when the world was oblivious to the things that were to come, Diana made public the decision of donating her personal library and archives, to the University of Texas-San Antonio where a special collection was created under the name of “Diana Kennedy Culinary Archive and Mexican Cookbook Collection”

This collection includes printed Mexican cookbooks from the 1800s, and personal archival material like photographs, scrapbooks, menus, and even letters she exchanged with Julia Child and other cooks and chefs, And the crowning jewels of this collection are the archives of her culinary and botanical research, field diaries and notes from each state of Mexico, and yes, that’s the very same material that helped the Commission for the Knowledge and Use of Biodiversity (CONABIO) to produce the foundation for the protection and study of Mexicos culinary biodiversity and as I discussed with the Director of Fundacion Tortilla de Maiz Mexicana Rafael Mier on episode 56 the input of this Commission using part of Diana’s work was key to ensure that the federal law to protect native varieties of corn was finally passed this year in Mexico.

Ever the keen observer and thanks to, I believe the decades of understanding Mexico from the inside out, I think Diana’s decision shows, I think, how much effort she put into making sure that her documents and library were safely preserved and rightfully put to good use straight away.

In an interview where she was asked bout why choosing the University of Texas and she said: “I think San Antonio seems to be a natural bridge between Mexico and the U.S.”

Diana is 97 years old, what will happen now?

To begin wrapping up this episode, Diana spent the most part of 56 years in Mexico travelling, documenting, farming, cooking and writing about the country’s food traditions which is of course is what she’s largely known for, but she has also been a very loud critic for the prevalent culture of unnecessary food waste at restaurant kitchens, shaming the extraordinary amount of single-use and highly contaminating materials at restaurant kitchens like plastic bags, containers and aluminium, she has also heavily criticised the fact that the majority of celebrity chefs have done very little to speak out about the flaws and crisis of the global food system of which the restaurant industry is part of.

The point is, that Diana’s opinions matter and they might appear as harsh but apparently, they need to be so. I think that the perspective from where she is coming from is from a person who deliberately has had a small carbon footprint and has had a sustainable life perhaps inspired by her interaction s with rural communities, her reflections and writing about their food practices that indeed are the product of resourcefulness, maximisation of natural and economic resources expressed through dishes that are local, seasonal and mostly balanced, which inevitably is going to contrast to the way large industrialised, modern cities operate, that is why she argues that within the food industry everyone should hold each other accountable act responsibly for the benefit of the environment, present and future generations.

During an interview, she gave for Eater on 2013 Diana said: “Nobody has done the work I have,” “And I’ve funded it all myself. That’s why I’m not rich.” To which Katharine Shilcutt who interviewed her, noted that even back then Diana was noticeably concerned about the financial safety of her project as any independent author can tell you: selling cookbooks and doing cooking classes is not necessarily a fastback to make you rich, and Diana even considered selling some of her precious historical cookbooks to keep her estate and projects afloat. Which we know now of course, that didn’t happen, but this goes to show you her priorities and how difficult it can be to ensure the continuity of projects.

History has shown us that humanity tends to be extraordinary slow at valuing and capitalising in realtime the extraordinary work of individuals like Diana Kennedy, and while she is recognised as a cookery teacher, culinary historian, chef, environmental activist and ethno-gastronome, but the fact that you pressed play and I am talking about it along with thousands of researchers, journalists, cooks and activists it has to be indicative of something good, and undoubtedly Elizabeth’s Carroll’s documentary has had a lot to do with this.

We hear too often expressions like, “we need more people like her” and “why aren’t many other Dianas?” And I think you can appreciate now that the complexity of her work goes way beyond the average process of recipe writing, and documenting the breadth and depth of one nation’s cuisine for decades requires a strong level of commitment, on the other hand while many people, around the word speak of her as the saviour of Mexican food you can argue that Mexican food saved her, it gave her a sense of purpose, agency and a career, it also fair to say that she benefited largely from a position of privilege as a foreign white woman with many connections and access to the international press and the book industry, and I think she has always been very aware of this but many not so much everybody else. Because she’s not the only person that has done extensive research about food studies in Mexico, there are dozens of Mexicans that have specialised in particular aspects and taken different approaches and dedicated their lives to it, like Guillermo Bonfil Batalla and his ample studies on corn, Virginia Garcia Acosta and her historical work on bread and wheat and Jeanette Long-Solís’ books on chillies, I could go on and on, so I think we are better off putting Diana’s work in context, seeing with a fair light her many contributions and use them to continue expanding on them.

Finally, I think is fair to say that you now have quite a lot to ponder about how to read Diana’s books, find out what is she communicating trough them and if you try the recipes she compiled you might as well take the chance to reflect on the fact that her legacy, along with the work of many other authors carries the voices of hundreds of generations of cooks and farmers who in the heat of their kitchens, the noise of the markets and the hopes and dreams that every crop cycle brings, builds a testament of the social and gastronomic memory of a nation.

How does that sound to you?

Get Diana’s books:

- The Cuisines of Mexico https://amzn.to/36UmFWH

- The Tortilla Book https://amzn.to/3ctCfK1

- Recipes from the Regional Cooks of Mexico https://amzn.to/3dw0gRY

(Includes the first three books) The Essential Cuisines of Mexico https://amzn.to/308yRl9

- The Art of Mexican Cooking https://amzn.to/306ifuu

- Mexican Regional Cooking https://amzn.to/3eN0yUN

- My Mexico: A Culinary Odyssey with More Than 300 Recipes https://amzn.to/3dvPs6q

- Nothing Fancy: Recipes and Recollections of Soul-Satisfying Food https://amzn.to/374owIA

- From my Kitchen: Techniques and Ingredients https://amzn.to/36W5vI8

- 10.Oaxaca al gusto: An Infinite Gastronomy https://amzn.to/3eN1kkK

Recommended articles about Diana Kennedy:

- Diana Kennedy Must Speak Loudly Before She Expires. The famous cookbook author and Mexican food maven on why preservation is more important now than ever. By Katharine Shilcutt. 10/28/2013 https://www.houstoniamag.com/arts-and-culture/2013/10/diana-kennedy-october-2013

- Diana Kennedy: La dama de la cocina mexicana (Spanish) Por Animal Gourmet https://www.animalgourmet.com/2013/08/26/diane-kennedy-la-dama-de-la-cocina-mexicana /

- Tus tortillas malas le molestan a Diana Kennedy (Spanish) Por Daniel Hernandez. 08 Marzo 2017 https://www.vice.com/es/article/gvmea3/tus-tortillas-pirata-molestan-a-diane-kennedy

- The Brit who saved Mexican food. Sarah Greenberg. Sun 12 Oct 2003 https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2003/oct/12/foodanddrink.features6#maincontent

- The Middle Beat: A Correspondent’s View of Mexico, Guatemala, and El Salvador (About Paul Kennedy) https://read.dukeupress.edu/hahr/article-standard/54/4/736/151243/The-Middle-Beat-A-Correspondent-s-View-of-Mexico